Combinatorial species

In combinatorial mathematics, the theory of combinatorial species is an abstract, systematic method for analysing discrete structures in terms of generating functions. Examples of discrete structures are (finite) graphs, permutations, trees, and so on; each of these has an associated generating function which counts how many structures there are of a certain size. One goal of species theory is to be able to analyse complicated structures by describing them in terms of transformations and combinations of simpler structures. These operations correspond to equivalent manipulations of generating functions, so producing such functions for complicated structures is much easier than with other methods. The theory was introduced by André Joyal.

The power of the theory comes from its level of abstraction. The "description format" of a structure (such as adjacency list versus adjacency matrix for graphs) is irrelevant, because species are purely algebraic. Category theory provides a useful language for the concepts that arise here, but it is not necessary to understand categories before being able to work with species.

Contents |

Definition of species

Any structure — an instance of a particular species — is associated with some set, and there are often many possible structures for the same set. For example, it is possible to construct several different graphs whose node labels are drawn from the same given set. At the same time, any set could be used to build the structures. The difference between one species and another is that they build a different set of structures out of the same base set.

This leads to the formal definition of a combinatorial species. Let  be the category of finite sets and bijections (the collection of all finite sets, and invertible functions between them). A species is a functor

be the category of finite sets and bijections (the collection of all finite sets, and invertible functions between them). A species is a functor

given a set A, it yields the set F[A] of F-structures on A. A functor also operates on bijections. If φ is a bijection between sets A and B, then F[φ] is a bijection between the sets of F-structures F[A] and F[B], called transport of F-structures along φ.

For example, the "species of permutations" maps each finite set A to the set of all permutations of A, and each bijection from A to another set B naturally induces a bijection from the set of all permutations of A to the set of all permutations of B. Similarly, the "species of partitions" can be defined by assigning to each finite set the set of all its partitions, and the "power set species" assigns to each finite set its power set.

There is a standard way of illustrating an instance of any structure, regardless of its nature. The diagram below shows a structure on a set of five elements: arcs connect the structure (red) to the elements (blue) from which it is built.

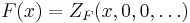

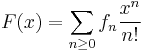

The choice of  as the category on which species operate is important. Because a bijection can only exist between two sets when they have the same size, the number of elements in F[A] depends only on the size of A. (This follows from the formal definition of a functor.) Restriction to finite sets means that |F[A]| is always finite, so it is possible to do arithmetic with such quantities. In particular, the exponential generating series F(x) of a species F can be defined:

as the category on which species operate is important. Because a bijection can only exist between two sets when they have the same size, the number of elements in F[A] depends only on the size of A. (This follows from the formal definition of a functor.) Restriction to finite sets means that |F[A]| is always finite, so it is possible to do arithmetic with such quantities. In particular, the exponential generating series F(x) of a species F can be defined:

where  is the size of F[A] for any set A having n elements.

is the size of F[A] for any set A having n elements.

Some examples:

- The species of sets (traditionally called E, from the French "ensemble", meaning "set") is the functor which maps A to {A}. Then

, so

, so  .

. - The species S of permutations, described above, has

.

.  .

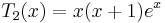

. - The species T2 of pairs (2-tuples) is the functor taking a set A to A2. Then

and

and  .

.

Calculus of species

Arithmetic on generating functions corresponds to certain "natural" operations on species. The basic operations are addition, multiplication, composition, and differentiation; it is also necessary to define equality on species. Category theory already has a way of describing when two functors are equivalent: a natural isomorphism. In this context, it just means that for each A there is a bijection between F-structures on A and G-structures on A, which is "well-behaved" in its interaction with transport. Note that species with the same generating function might not be isomorphic, but isomorphic species do always have the same generating function.

Basic operations

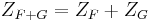

Addition of species is defined by the disjoint union of sets, and corresponds to a choice between structures. For species F and G, define (F + G)[A] to be the disjoint union (also written "+") of F[A] and G[A]. It follows that (F + G)(x) = F(x) + G(x). As a demonstration, take E+ to be the species of non-empty sets, whose generating function is E+(x) = ex − 1, and 1 the species of the empty set, whose generating function is 1(x) = 1. It follows that E = 1 + E+: in words, "a set is either empty or non-empty". Equations like this can be read as referring to a single structure, as well as to the entire collection of structures.

Multiplying species is slightly more complicated. It is possible to just take the Cartesian product of sets as the definition, but the combinatorial interpretation of this is not quite right. (See below for the use of this kind of product.) Rather than putting together two unrelated structures on the same set, the multiplication operator uses the idea of splitting the set into two components, constructing an F-structure on one and a G-structure on the other.

This is a disjoint union over all possible binary partitions of A. It is straightforward to show that multiplication is associative and commutative (up to isomorphism), and distributive over addition. As for the generating series, (F · G)(x) = F(x)G(x).

The diagram below shows one possible (F · G)-structure on a set with five elements. The F-structure (red) picks up three elements of the base set, and the G-structure (light blue) takes the rest. Other structures will have F and G splitting the set in a different way. The set (F · G)[A], where A is the base set, is the disjoint union of all such structures.

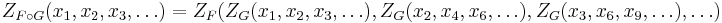

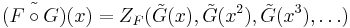

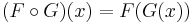

Composition, also called substitution, is more complicated again. The basic idea is to replace components of F with G-structures, forming (F∘G). As with multiplication, this is done by splitting the input set A; the disjoint subsets are given to G to make G-structures, and the set of subsets is given to F, to make the F-structure linking the G-structures. It is required for G to map the empty set to itself, in order for composition to work. The formal definition is:

Here, P is the species of partitions, so P[A] is the set of all partitions of A. This definition says that an element of (F∘G)[A] is made up of an F-structure on some partition of A, and a G-structure on each component of the partition. The generating series is  .

.

One such structure is shown below. Three G-structures (light blue) divide up the five-element base set between them; then, an F-structure (red) is built to connect the G-structures.

These last two operations may be illustrated by the example of trees. First, define X to be the species "singleton" whose generating series is X(x) = x. Then the species Ar of rooted trees (from the French "arborescence") is defined recursively by Ar = X · E(Ar). This equation says that a tree consists of a single root and a set of (sub-)trees. The recursion does not need an explicit base case: it only generates trees in the context of being applied to some finite set. One way to think about this is that the Ar functor is being applied repeatedly to a "supply" of elements from the set — each time, one element is taken by X, and the others distributed by E among the Ar subtrees, until there are no more elements to give to E. This shows that algebraic descriptions of species are quite different from type specifications in programming languages like Haskell.

Likewise, the species P can be characterised as P = E(E+): "a partition is a pairwise disjoint set of nonempty sets (using up all the elements of the input set)". The exponential generating series for P is  , which is the series for the Bell numbers.

, which is the series for the Bell numbers.

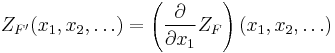

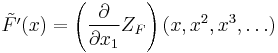

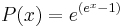

Differentiation is an operation that makes more sense for series than it does for species. To differentiate an exponential series, the sequence of coefficients needs to be shifted one place to the "left" (losing the first term). This suggests a definition for species: F' [A] = F[A + {*}], where {*} is a singleton set and "+" is disjoint union. The more advanced parts of the theory of species use differentiation extensively, to construct and solve differential equations on species and series. The idea of adding (or removing) a single part of a structure is a powerful one: it can be used to establish relationships between seemingly unconnected species.

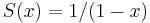

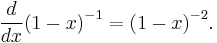

For example, consider a structure of the species L of linear orders—lists of elements of the ground set. Removing an element of a list splits it into two parts (possibly empty); in symbols, this is L' = L·L. The exponential generating function of L is L(x) = 1/(1 − x), and indeed:

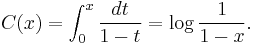

The species C of cyclic permutations takes a set A to the set of all cycles on A. Removing a single element from a cycle reduces it to a list: C' = L. We can integrate the generating function of L to produce that for C.

Further operations

There are a variety of other manipulations which may be performed on species. These are necessary to express more complicated structures, such as directed graphs or bigraphs.

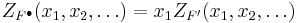

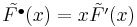

Pointing selects a single element in a structure. Given a species F, the corresponding pointed species F• is defined by F•[A] = A × F[A]. Thus each F•-structure is an F-structure with one element distinguished. Pointing is related to differentiation by the relation F• = X·F' , so F•(x) = x F' (x). The species of pointed sets, E•, is particularly important as a building block for many of the more complex constructions.

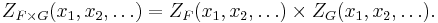

The Cartesian product of two species is a species which can build two structures on the same set at the same time. It is different from the ordinary multiplication operator in that all elements of the base set are shared between the two structures. An (F × G)-structure can be seen as a superposition of an F-structure and a G-structure. Bigraphs could be described as the superposition of a graph and a set of trees: each node of the bigraph is part of a graph, and at the same time part of some tree that describes how nodes are nested. The generating function (F × G)(x) is the Hadamard or coefficient-wise product of F(x) and G(x).

The species E• × E• can be seen as making two independent selections from the base set. The two points might coincide, unlike in X·X·E, where they are forced to be different.

As functors, species F and G may be combined by functorial composition: ![(F \Box G) [A] = F[G[[A]]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bf4aacfd42eae83a6bafd826faa143ff.png) (the box symbol is used, because the circle is already in use for substitution). This constructs an F-structure on the set of all G-structures on the set A. For example, if F is the functor taking a set to its power set, a structure of the composed species is some subset of the G-structures on A. If we now take G to be E• × E• from above, we obtain the species of directed graphs, with self-loops permitted. (A directed graph is a set of edges, and edges are pairs of nodes: so a graph is a subset of the set of pairs of elements of the node set A.) Other families of graphs, as well as many other structures, can be defined in this way.

(the box symbol is used, because the circle is already in use for substitution). This constructs an F-structure on the set of all G-structures on the set A. For example, if F is the functor taking a set to its power set, a structure of the composed species is some subset of the G-structures on A. If we now take G to be E• × E• from above, we obtain the species of directed graphs, with self-loops permitted. (A directed graph is a set of edges, and edges are pairs of nodes: so a graph is a subset of the set of pairs of elements of the node set A.) Other families of graphs, as well as many other structures, can be defined in this way.

Types and unlabelled structures

Instead of counting all the possible structures that can be built on some set, we often want to count only the number of different "shapes" of structure. Consider the set of rooted trees on the set A = {a, b, c}. There are nine of these, which can be grouped into two classes by tree shape. There are:

- Six trees with three levels:

- a → b → c

- a → c → b

- b → a → c

- b → c → a

- c → a → b

- c → b → a

- Three trees with two levels: (not six, because subtrees are not in any order)

- b ← a → c

- a ← b → c

- a ← c → b

There is an exact correspondence between trees in the first class and permutations of A. Any of these trees can be constructed from any of the others, by permuting the labels on its nodes. For any two trees s and t in this class, there is some permutation σ in the symmetric group SA which acts on s to give t: Ar[σ](s) = t. The same holds for the second class of trees. This property can be used to define an equivalence relation on Ar[A], dividing it into the two parts listed above. These equivalence classes are the isomorphism types of Ar-structures of order 3.

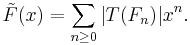

Formally, when F is a species, we define T(Fn) to be the quotient set F[{1, ..., n}]/~ of types of F-structures of order n, where "~" is the relation "s ~ t if and only if there is some σ in Sn such that F[σ](s) = t". As with the exponential generating functions, the size of T(Fn) depends only on the value of n and the definition of F. It is the set of unlabelled F-structures on any set of size n.

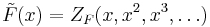

The isomorphism type generating series of F is:

Manipulations of these functions are done in essentially the same way as for the exponential generating functions. There are a few differences in how some of the operations translate into operations on type generating series. Addition and multiplication work as expected, but the more complicated operations need some more sophisticated mathematical tools for their proper definitions.

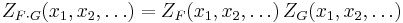

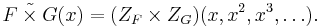

There is a much more general series, called the cycle index series, for each species, which contains all the information in the previously-defined series, and more. Any permutation σ of a finite set A with n elements can be decomposed, uniquely, into a product of disjoint cycles. Letting σi be the number of cycles of length i in the decomposition of σ ∈ Sn, the cycle type of σ is defined to be the sequence (σ1, σ2, ..., σn). Now let Fix(σ) be the set of elements fixed by σ — that is, the elements x of A where σ(x) = x. Then the cycle index series of F is:

Note that |Fix(F[σ])| is the number of F-structures on A = {1, ..., n} for which σ is an automorphism.

It follows immediately that

and

for any species F. The cycle index series follows these rules for combinatorial operations on species F and G:

Then the rules for type generating series can be given in terms of these:

Class of all species

There are many ways of thinking about the class of all combinatorial species. Since a species is a functor, it makes sense to say that the category of species is a functor category whose objects are species and whose arrows are natural transformations. This idea can be extended to a bicategory of certain categories, functors, and natural transformations, to be able to include species over categories other than  . The unary and binary operations defined above can be specified in categorical terms as universal constructions, much like the corresponding operations for other algebraic systems.

. The unary and binary operations defined above can be specified in categorical terms as universal constructions, much like the corresponding operations for other algebraic systems.

Though the categorical approach brings powerful proof techniques, its level of abstraction means that concrete combinatorial results can be difficult to produce. Instead, the class of species can be described as a semiring — an algebraic object with two monoidal operations — in order to focus on combinatorial constructions. The two monoids are addition and multiplication of species. It is easy to show that these are associative, yielding a double semigroup structure; and then the identities are the species 0 and 1 respectively. Here, 0 is the empty species, taking every set to the empty set (so that no structures can be built on any set), and 1 is the empty set species, which is equal to 0 except that it takes  to

to  (it constructs the empty set whenever possible). The two monoids interact in the way required of a semiring: addition is commutative, multiplication distributes over addition, and 0 multiplied by anything yields 0.

(it constructs the empty set whenever possible). The two monoids interact in the way required of a semiring: addition is commutative, multiplication distributes over addition, and 0 multiplied by anything yields 0.

The natural numbers can be seen as a subsemiring of the semiring of species, if we identify the natural number n with the n-fold sum 1 + ... + 1 = n 1. This embedding of natural number arithmetic into species theory suggests that other kinds of arithmetic, logic, and computation might also be present. There is also a clear connection between the category-theoretic formulation of species as a functor category, and results relating certain such categories to topoi and Cartesian closed categories — connecting species theory with the lambda calculus and related systems.

Given that natural number species can be added, we immediately have a limited form of subtraction: just as the natural number system admits subtraction for certain pairs of numbers, subtraction can be defined for the corresponding species. If n and m are natural numbers with n larger than m, we can say that n 1 − m 1 is the species (n − m) 1. (If the two numbers are the same, the result is 0 — the identity for addition.) In the world of species, this makes sense because m 1 is a subspecies of n 1; likewise, knowing that E = 1 + E+, we could say that E+ = E − 1.

Going further, subtraction can be defined for all species so that the correct algebraic laws apply. Virtual species are an extension to the species concept that allow inverses to exist for addition, as well as having many other useful properties. If S is the semiring of species, then the ring V of virtual species is (S × S) / ~, where "~" is the equivalence relation

- (F, G) ~ (H, K) if and only if F + K is isomorphic to G + H.

The equivalence class of (F, G) is written "F − G". A species F of S appears as F − 0 in V, and its additive inverse is 0 − F.

Addition of virtual species is by component:

- (F − G) + (H − K) = (F + H) − (G + K).

In particular, the sum of F − 0 and 0 − F is the virtual species F − F, which is the same as 0 − 0: this is the zero of V. Multiplication is defined as

- (F − G)·(H − K) = (F·H + G·K) − (F·K + G·H)

and its unit is 1 − 0. Together, these make V into a commutative ring, which as an algebraic structure is much easier to deal with than a semiring. Other operations carry over from species to virtual species in a very natural way, as do the associated power series. "Completing" the class of species like this also means that certain differential equations insoluble over S do have solutions in V.

Generalizations

Species need not be functors from  to

to  : other categories can replace these, to obtain species of a different nature.

: other categories can replace these, to obtain species of a different nature.

- A species in k sorts is a functor

. Here, the structures produced can have elements drawn from distinct sources.

. Here, the structures produced can have elements drawn from distinct sources. - A functor to

, the category of R-weighted sets for R a ring of power series, is a weighted species.

, the category of R-weighted sets for R a ring of power series, is a weighted species. - A tensorial species is a functor into the category of finite-dimensional vector spaces over the complex numbers.

Software

Operations with species are supported by Sage[1] and, using a special package, also by Haskell.[2][3]

Notes

- ^ Sage documentation on combinatorial species.

- ^ Haskell package species.

- ^ Brent A., Yorgey (2010). Species and functors and types, oh my!. ACM. pp. 147–158. doi:10.1145/1863523.1863542. ISBN 978-1-4503-0252-4.

References

- André Joyal, Une théorie combinatoire des séries formelles, Advances in Mathematics 42:1-82 (1981).

- François Bergeron, Gilbert Labelle, Pierre Leroux, Théorie des espèces et combinatoire des structures arborescentes, LaCIM, Montréal (1994). English version: Combinatorial Species and Tree-like Structures, Cambridge University Press (1998).

- François Bergeron, Species and Variations on the Theme of Species, invited talk at Category Theory and Computer Science '04, Copenhagen (2004). Slides (pdf).

- Marcelo Aguiar, Swapneel Mahajan, Monoidal functors, species and Hopf algebras, CRM Monograph Series Volume 29. A co-publication of the AMS and Centre de Recherches Mathématiques. Expected publication date is November 19, 2010. pdf

- Federico G. Lastaria, An invitation to Combinatorial Species.

See also

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Species" from MathWorld.

![(F \cdot G)[A] = \sum_{A=B%2BC} F[B] \times G[C].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a62ceb8bfbe034364e626d269bb0e84e.png)

![(F \circ G)[A] = \sum_{\pi \in P[A]} (F[\pi] \times \Pi_{B \in \pi} G[B]).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a1d45f35e71073d476630e24f06f3397.png)

![Z_F(x_1, x_2, \dots) = \sum_{n \ge 0} \frac{1}{n!} \left( \sum_{\sigma \in S_n} |\mathrm{Fix}(F[\sigma])| x_1^{\sigma_1} x_2^{\sigma_2} \cdots \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/423cbbb5b2b4009e376a5a19f5dd3b6e.png)